The Birth of Science

[History of Science]

Between 250,000 and 30,000 years ago a subspecies of Homo sapiens, commonly known as neanderthals, inhabited a territory from England across southern Europe into Asia. They built hut-like structures, hunted big game, and developed ceremonial rituals. The remains of this relatively short-lived group reflect a consciousness akin to our own. They clearly had a sense of the passage of time and physical mortality. Ceremonial burials show a concern with life after death. We find in the neanderthals the signs of a greater consciousness of the subtleties of the world and, in this greater consciousness, the roots of our own religious and scientific thinking. The subspecies to which all living humans belong, Homo sapiens sapiens, probably emerged somewhere around 100,000 years ago, and forms a cultural, and probably intellectual, continuum with the neanderthals.

We really don't know much concerning the specific world-views of early humans. We have only some burial sites, figurines, and cave paintings to provide tantalizing hints. These suggest that their thinking was of a type that would now be called magical or superstitious. It seems clear that these stone-age people sought to employ magical rituals to influence the external world, hoping to positively affect hunting, fertility, and other survival-related aspects of their lives. Though such thinking may seem primitive to us, it clearly reflects a mind attempting to bring order into the universe.

Many scholars believe that the magical, animistic approach to understanding the world led directly to the mythical approach. Repeated attempts at magic would probably give birth to ritual. Even when such a ritual outlived its original purpose or when its true meaning had become obscured over time, it might still remain a psychologically essential part of the culture. An appropriate myth could provide justification for its continuance. In any case, with the coming of civilization some 10,000 years ago, it is clear that the magical thinking of the earliest peoples had already evolved into mythology.

Myths, though differing in their local details, have some common threads running through them. Often powerful non-human, but anthropomorphic, figures create and control the world and its inhabitants. Myth is always related to creation; it tells how something came into existence (the universe, human beings), or how a pattern of behavior was established. This History is considered to be absolutely true and sacred.

Surely myth arose from our need to make sense of the world as a whole, and, particularly, of our place as human beings in it. We see in myth attempts to find cause and effect explanations for the experienced world. Early people wove basic sensory knowledge of the world into a pattern that seems reasonable. (The Mesopotamian creation myth used their knowledge of how silt deposits form land where fresh and salt water meet.) Thus, Although there are some obvious differences between the mytho-poetic approach and the scientific approach, we can also see connections. Myths are the first rungs on the ladder of discovery. Embedded within them are basic truths about both the universe and the human condition.

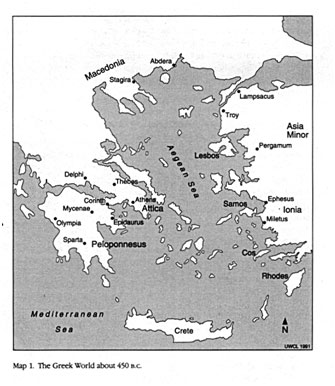

Science had its beginnings in ancient Greece. Although it is probably an exaggeration to think in terms of "the Greek miracle" or of "motherless

Athena," as is frequently done, it is clear that about 600 B.C. a new approach to understanding the universe emerged. Although the Greeks had their myths, they went beyond the myths to search for physical explanations. Unlike earlier cultures, they were not content to explain the universe in terms of the actions of the gods; the Greeks insisted on thinking in terms of natural processes. These protypical scientists made the remarkable assumption that an underlying rational unity and order existed within the flux and variety of the world. Nature was to be explained in terms of nature itself, not of something fundamentally beyond nature, and in impersonal terms rather than by means of personal gods and goddesses. Science was born here, not motherless, to be sure, but nonetheless a new and distinctly different way of looking at the world.

Thales (624-547 B.C.) was born in the Greek city of Miletus across the Aegean Sea from the Greek mainland. The inhabitants of this region were known as Ionians (Greeks who fled the Dorian invasion). Its location on the coast of Asia Minor provided Thales with exposure to the cultures of both the Babylonians and the Egyptians, and in fact, he visited both countries. It was his knowledge of Babylonian astronomy that allowed him to make his famous prediction of the solar eclipse of May 28, 585 B.C.

We consider Thales the first scientist because, as far as we can tell from the admittedly incomplete historical record, he was the first to approach the world from a scientific perspective. He wondered how the universe came to be and came up with an answer far different from that depicted in the creation of the gods myth of Hesiod's Theogony (8th century B.C.). It seemed to him that all things either came from moisture or were sustained by moisture. So he concluded that the universe grew from water. According to Thales the earth was a flat disc floating on a sea of water. The

unique element in the cosmology of Thales was the idea that the universe developed over time through natural processes from some undifferentiated state. The first recorded use of a physical model in explaining a natural phenomenon is Thales belief that earthquakes were caused by disturbances in the water that supported the earth.

As with any human being, Thales was of course constrained by the level of knowledge available at the time and by the cultural and intellectual context in which he found himself. It is clear that the earlier mythopoetic tradition exerted a strong influence on him. For example, from Aristotle we learn that included in Thales' metaphysical and cosmological doctrines was the idea that inanimate objects that move and are moved (magnets and iron, amber and wool) possess souls. It's hard to know what Thales meant by this exactly, but on the surface of it, it doesn't strike us as scientific.

There is an additional, more subtle, nonscientific element in Thales view. His two primary assumptions about the origin of the world were 1) that the present world order arose out of some preexistent state and thus had a beginning in time, and 2) that this world order occurred by a process of differentiation from a previous state. These beliefs are not suggested by an unbiased observation of nature itself, at least not as it was known to Thales. He must have come to this conclusion for deeper, perhaps subconscious, reasons. Similar psychological pre-dispositions have continued to play a role in science through to the present day.

Thales had a student named Anaximander (610-546 B.C.). He introduced the notion of a spherical universe, an idea that survived for more than 2000 years. He saw the earth as suspended in space (rather that floating on water). He also believed that living creatures arose from the moist elements when it had been partially evaporated by the sun. According to Anaximander, humans in the beginning resembled fish.

In the second half of the the fifth century, the materialism of the sixth century was adopted and extended by the atomist Leucippus of Miletus (fl. 440 B.C.E.) and Democrutus of Abdera (c. 470 – c. 400 B.C.). Democritus constructed a complex explanation of all phenomena in purely materialistic terms: The world was composed exclusively of uncaused and immutable material atoms. These invisibly minute and indivisible particles perpetually moved about in a boundless void and by their random collisions and varying combinations produced the phenomena of the visible world. In the words of Democritus, “nothing exists except atoms and the void; all else is mere opinion.”

It is interesting to note that a central concept in the thinking of Thales, Anaximander, and Democritus is that there is no real distinction between the terrestrial and celestial realms. Only later did Greek thinking regress to needing a fifth essence (the quintessence) for celestial objects.

The earlier and simpler phase of Greek thought terminates with the fifth century in a thinker of an entirely different type, Socrates (470-399 B.C.). With Socrates and his student Plato (427-347 B.C.), we have a unique synthesis of Greek science and Greek religion. The visible world contains within it a deeper meaning, in some sense both rational and mythic in character, which is reflected in the empirical order but which emanates from

an eternal dimension that is both source and goal of all existence. This is described in some detail in Tarnas, The Dual Legacy, pp 69-72.

With Aristotle (348-322 B.C.), the pendulum began to swing back toward the more down-to-earth perspective of the presocratics. Plato asserted the existence of archetypal Ideas or Forms as primary, while the visible objects of conventional reality are their direct derivatives. These Ideas, according to Plato, possess a quality of being, a degree of reality, that is superior to that of the concrete world. On the other hand, Aristotle assumed that true reality was the perceptible world of concrete objects, rather than the imperceptible world of Plato’s eternal Ideas. Aristotle placed a new and fruitful stress on the value of observation and classification. He provided a language and logic, a foundation and structure, and, not least, a formidably authoritative figure without which the philosophy, theology, and science of the West could not have developed as they did. The Aristotelian system of physics, in a more or less modified form, was absorbed by the various philosophical schools of antiquity and played a very important part in the history of Christian thought. Its fundamental bases were: